Ooooooooo

Fair warning: This post discusses death and end of life care. If that’s not for you, then perhaps skip this post and read the next one.

When I was first asked about planning for eventual death, the mind wanders and you inevitably start thinking about how you might like to die yourself. Something involving two monster trucks and a giant see-saw, or becoming the first human cannonball to plop like a sugarlump into the cauldron of Krakatoa, or be frozen in a vat of semi-runny Sainsbury’s strawberry jam, so that you can be defrosted like Demolition Man. In reality though death planning in a healthcare context is far more serious.

Planning for when we die, requires thinking responsibly about how we can both stage-manage our own exit, as well as how we can make the bereavement journey easier for our loved ones.

My own ancestors feel a bit like two or three 500 piece puzzles jumbled together. The belongings I have inherited have gone uncurated for over a century, meaning that a napkin ring and a Bible from 1814 hover around the house more like lost property than treasured heirlooms. These were clearly significant objects for my ancestors who are an utterly incomprehensible mixture of surgeons, rowers, farmers, army officers, and bricklayers from every corner of the British Isles and beyond. These objects also serve as a lens through which I see them now. How can I not? It’s also easy to grow a myth on the Petri dish of one object of theirs – like the Victorians taking the horn of an iguanodon and extrapolating an entire, wonkily shaped giant lizard.

In our own death planning or “death plan” for short, we can shape this lens ourselves. We can eliminate those moments of chance encounter with our belongings after we’ve gone. We can thereby limit their exposure to something that is more within the realm of their control.

According to the NHS’s guidance this can be done through the creation of a “memory box”. Inside the memory box can be things help to remind people of key aspects of who you were. It could also be things that hold historical as well as sentimental value like a diary, or an autographed set list from a gig or a postcard to a loved one that has outlived its initial purpose and now offers a window into your future hopes for its recipient. The memory box can condense your life down to just a few objects. It’s hard not to think of William Carlos Williams‘ maxim “no ideas but in things”. Who else, but the one poet who has made us think about the undocumented significance of a Red Wheelbarrow for three quarters of a century.

While it might be one thing to leave something behind, but death planning is also about the tougher, more intimate and bodily asks. These are all decisions related to what should be done when many of the lights are off, but some yet remain switched on while you’re getting ready to leave.

If you need end of life care, you want to be able to make those calls in advance while you’re still in a position to make reasonable decisions about future scenarios. It’s easy to consider the future existential until the worst happens. In fact this overly optimistic outcome is very natural and is a well-known cognitive bias known as “optimism bias“. It’s the same reason we buy scratchcards, or blow on the dice at a casino, we vastly overestimate our ability to be lucky and to come out on top.

If you have advanced dementia and require a ventilator to continue living, it’s better to know the right call to make now rather than create a complex situation for your family in the future. You also want to be able to think about any legal and financial provisions for your family, including making a will. Finally, although bleakly comic, the most creative aspect to death planning is planning your own funeral and one that doesn’t involve playing the theme from Countdown or the still extremely popular choice of Queen’s ‘Another One Bites the Dust‘.

These subjects are extremely difficult to discuss with relative strangers and, on top of that, we need to do this in a way that is creative and that utilises two artforms at the same time: poetry and visual art.

I’ve largely steered away from tackling this subject too directly. At Senses, we used the river of life exercise to help contextualise the journeys of people’s lives. At Marske on the March and with the Age UK group who meet at the Marske Cricket Club, we want to be able to ask questions that feel conducive to starting a conversation about the future, but that equally will give us some creative responses. In the end I opted for a combination of trivia and personal questions – to go along with the pub quiz that the group already enjoy during our workshop time. Questions about jetpacks and flying cars sit alongside more philosophical ones about how they hope the future will shake out. I don’t want to disrupt that personal sense of overestimation too much, but I do want to give participants a realistic opportunity to talk about their experiences and in light of that, their thoughts and feelings about the future. This means going largely one to one and or table by table around the room to ask them what they think. Here’s an example sheet.

In this example, I spoke to a participant about their feelings. The first thing they picked up on was that they are scared of heights so the prospect of flying in a car was actually quite terrifying for them. Even despite this, they also recognised that yes, it might be that there will be a mass-produced flying car. It allowed me to ask more questions about how the future might disagree with their preferences and to flip that around and to ask a bit about how the would like the future to be. These questions made them think about their kids and how much they had been anxious to keep their kids safe earlier in their lives. They felt that if they could not do something themselves then their kids would also not be able to do something – whether that’s working in a hospital setting, or as a market analyst, etc. Now they were older, they recognised that they had let their children do more and work outside of that safety and comfort zone and that this has been a very positive step. It’s also had the added effect of making them feel more positive about the future.

Thinking about Mars was a far bigger question. It feels too cosmic and beyond our control. This was also a common theme among participants – let the so-called “men who know what they’re doing” sort it out. It felt too existential and at the same time quite worrying. If you’re on Mars, where do you hang up the washing? For me, listening to this, I understand the nuances of the generational difference even as I can’t help but feel moved by the pain of that difference, but it is also revealing of the hurdle there is in conceptualising the idea of how important your own life is and the value of your own contribution to society. If that contribution is given further validity, then I believe that will also do a great deal to support both the mental and physical wellbeing of the community as well as to give members of the community a greater sense of autonomy in their own lives and ownership over their decisions and decision-making.

Lastly, living forever, you can see a similar conflict here. These responses were not unanimous across the group. Some people circled “No” for every answer and told me about their favourite places to go on holiday, or a trip to the dentist’s. Others, particularly amongst the men, stressed the importance of friendship and the keeping yourself motivated and showing up, week in week out and keeping busy. That more immediate future was significantly easier to negotiate than the longer term questions, particularly those that implied any sort of change in cognitive or physical function. This is harder to understand, but on instinct alone, subjectively I would estimate that this has more to do with pride in physical ability and that being synonymous with the traditional role of the patriarchal heir and “provider” and that very outdated role being tied very strongly to a sense of physical dignity too. Potentially this is an area around which an artist could design a workshop in the future, to encourage further exploration around the imagined ideal of living forever and the reality.

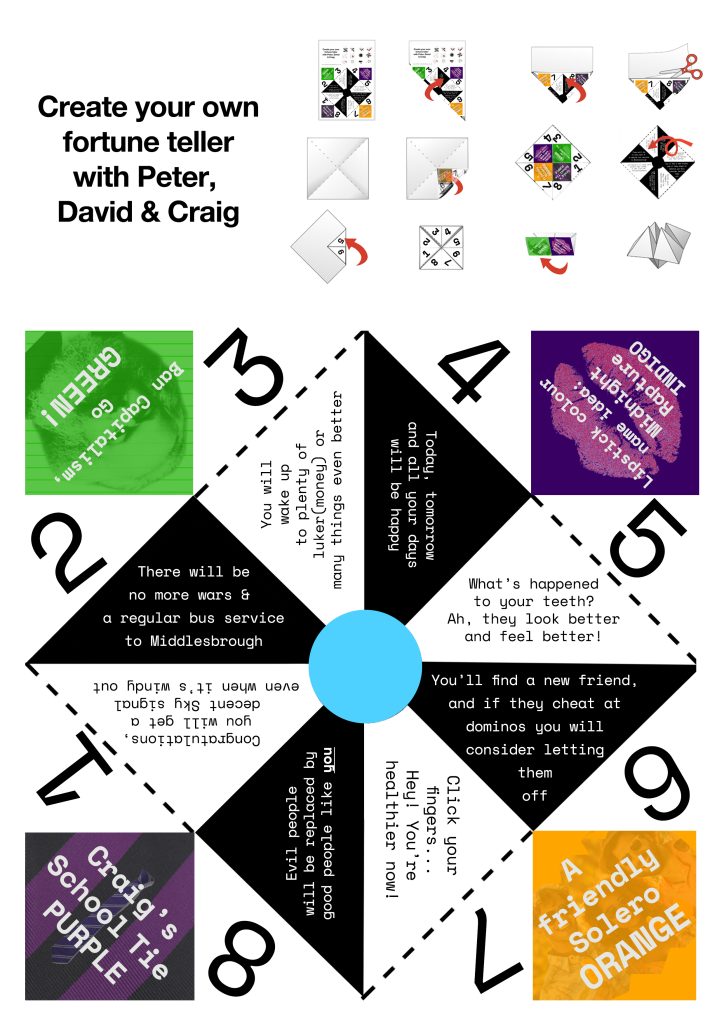

Using these responses as a basis, I created a series of fortune tellers that participants can use and play with as well as giving them printed card versions that they can cut and fold for themselves.