Rivers of Life and Meaning

“Pathmaker, there is no path,

You make the path by walking.

By walking, you make the path … ”

Antonio Machado

Working in children’s theatre for the first time, I had to learn the ropes. First comes the writing, you open the computer and your fingers dart across the keys flicked by the subconscious like Subbuteo players minding the goal. You might worry for the words terribly until they kick the ball into the network of the mind of someone else, everything until then feels somewhere between manager and parent. Learning to write and then perform in children’s theatre, there is a new extension to that responsibility, to embody the language, orchestrate its ontology in a live space through the use of cues and electronics. That parental and managerial worry continues out of you like breath on a cold day.

We took the Devil’s picnic blanket of the M1, driving for miles to a giant, strip-lit music store outlet near York to retrieve a portable speaker and wireless microphone. I learned the ropes of the mic, the way my voice enlarged and reverberated, tuttered, “eemed” and zipped, “aarked” and rub-a-dub-dubbed in different spaces. I had to learn how to design the sound of a rocket engine, layering launch noises, staggered and out of phase until the cardboard boxes in my living room buzzed and trembled with just the right amount of rumble and thrill. Months later, with everything powered down, my niece came to stay and she found confetti from one of our shows and gradually inserted pieces of that confetti into the hollow cab of the speaker. This spontaneous act is really the point of the story. The mind of a child can be a bit of a black box. Was she being a vandal or just tidying up? What is automatic? What is symptomatic? What is intentional? What is nurture, nature or idiopathic and confounding? In fact, is there a right way to analyse a child’s mind at all?

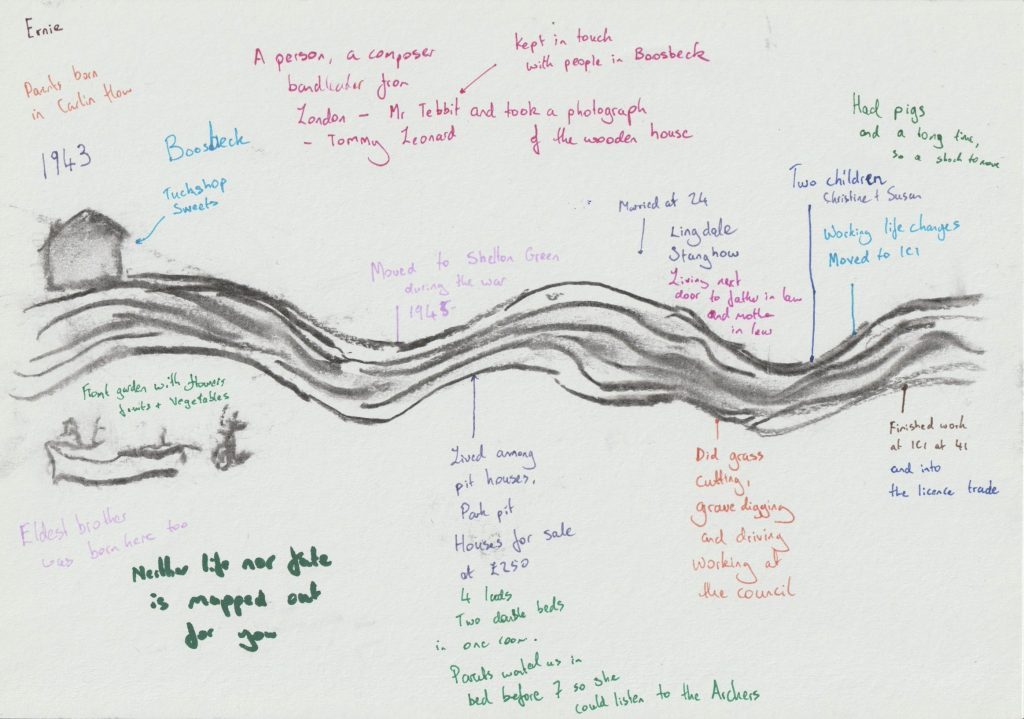

In 1926 Professor Florence Goodenough developed a test to establish the psychological concerns and understanding of children. It was called the DAP or “Draw-a-Person” test. This test was seen as a way to gain insights into a kid’s cognition and a sense of their personality. Did the child draw large eyes, or no eyes at all? Did bigger eyes mean the child was more paranoid? Did the child draw feet, face or hands with distortions or hurried lines? Did these mean the child had a warped, left out in the rain sense of self? Or was this indicative of neglect? In combination with conversations, more insights could be gained. The DAP was later developed into the HTP or “House-Tree-Person” test. The HTP test is supposed to show 1. the house – which represents an expression of family and family values, 2. the tree – a sense of social connection, with more branches meaning more connection and 3. the person – the idea of the artist’s self, who are we and what do we think of ourselves? It feels intuitively accurate. The child artist physically doing the drawing is none the wiser. To our more contemporary way of thinking, part of this feels more like reading tea leaves than robust science. The evidence to support any correlation between the pile of twigs style drawing of a human and their exposure to trauma or more blandly, exposure to a pile of twigs with human characteristics is relatively slim. What happens though, when we start from a position of telling the artist what they are drawing from the very beginning, emphasising that this is an act of autobiography? This is where a new exercise, aimed at adults comes in. It’s called The River of Life. This exercise was proposed by Emma. In conversation, we work with participants to draw a river of their lives using charcoal and coloured pens.

Working with older groups, the JSNA specifies that we need to ask them about the end of their life. How do we put our own lives in some perspective? At the time, we were just happily working through the hours like pieces of confetti, putting them successively, one after another, day by day into the unplugged speaker cab of our years on Earth, not really thinking that one day our lives would end potentially in a way as abrupt and mute as the short circuit of a sensitive piece of audio electronics.

I’m stretching the metaphor, but the principle is sound. How we plan the last chapter of our lives perhaps becomes easier, when we can take stock of the journey so far. Knowing the river serves this purpose of organising the narrative of our lives and its course, allows us to take pride and joy in our achievements and to think more clearly and perspicuously about the future. This is where there appears to be a strong overlap between drawing and writing as means of creative expression and drawing and writing for therapeutic purposes, where at least half of the intended readership is our own mind.

It’s hard to know the precise correlation, but I like to think, by virtue of knowing the goal of the exercise, the participant is more inclined to read their own life into it. We will have to save a more forensic analysis until we get to the more thorough evaluations later in the project. For now, though, I can tell you that each of our participants were very keen to keep going after the ring of the final bell and it started a number of very in-depth, personal and special conversations about meeting new friends, valuing community and finding intense joy in life.